Robert Graves on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Common Asphodel: Collected Essays on Poetry 1922–1949''. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1949.

* ''Occupation: Writer''. New York: Creative Age Press, 1950; London: Cassell, 1951. * ''

Robert Graves Trust and Society Information Portal

Robert Graves Foundation

Profile at Poetry Foundation

Profile, poems written and audio at poets.org

Profile, poems written and audio at Poetry Archive

Gallery of Graves's portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London

Papers of Robert Graves: Correspondence, 1915–1996

* Translated Penguin Books – a

Penguin First Editions

reference site of early first edition Penguin Books.

The Robert Graves Digital Archive

by the

Robert Graves collection

at University of Victoria, Special Collections

Robert Graves Papers

at Southern Illinois University Carbondale Special Collections Research Center * * * William S. Reese Collection of Robert Graves. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. *

1965 BBC television interview

(29 mins) * *

* ttp://www.robertgravesoratorio.co.uk "The Cool Web: A Robert Graves Oratorio"– First World War commemoration piece based on texts from Robert Graves's poems {{DEFAULTSORT:Graves, Robert 1895 births 1985 deaths 20th-century atheists 20th-century British non-fiction writers 20th-century British poets 20th-century British short story writers 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English poets 20th-century translators Alumni of St John's College, Oxford Bisexual men Bisexual writers British Army personnel of World War I Cultural critics English atheists English expatriates in Spain English historical novelists English LGBT novelists English LGBT poets English literary critics English male non-fiction writers English male novelists English male poets English male short story writers English memoirists English people of German descent English people of Irish descent English short story writers English World War I poets Graves family James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Matriarchy Olympic competitors in art competitions Oxford Professors of Poetry People educated at Charterhouse School People educated at Copthorne Preparatory School People educated at King's College School, London People from Wimbledon, London People with post-traumatic stress disorder Prix Italia winners Royal Welch Fusiliers officers Translators of Omar Khayyám Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Writers of style guides Military personnel from Surrey

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet,

accessed 27 July 2010

/ref>

Immediately after the war, Graves with his wife, Nancy Nicholson had a growing family, but he was financially insecure and weakened physically and mentally:

Immediately after the war, Graves with his wife, Nancy Nicholson had a growing family, but he was financially insecure and weakened physically and mentally:

''Time'', 31 May 1968 The translation quickly became controversial; Graves was attacked for trying to break the spell of famed passages in Edward FitzGerald's Victorian translation, and L. P. Elwell-Sutton, an orientalist at

documentary film historical novelist

This page provides a list of novelists who have written historical novels. Countries named are where they ''worked'' for longer periods. Alternative names appear before the dates.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

...

and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves

Alfred Perceval Graves (22 July 184627 December 1931), was an Anglo-Irish poet, songwriter and folklorist. He was the father of British poet and critic Robert Graves.

Early life

Graves was born in Dublin and was the son of The Rt Rev. Cha ...

, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celticists and students of Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally passed down orally in the prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later written down in the early medieval era by C ...

. Graves produced more than 140 works in his lifetime. His poems, his translations and innovative analysis of the Greek myths, his memoir of his early life—including his role in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

—''Good-Bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I ha ...

'', and his speculative study of poetic inspiration ''The White Goddess

''The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth'' is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by author and poet Robert Graves. First published in 1948, the book is based on earlier articles published in ''Wales'' magaz ...

'' have never been out of print. He is also a renowned short story writer, with stories such as "The Tenement" still being popular today.

He earned his living from writing, particularly popular historical novels such as ''I, Claudius

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Ro ...

''; '' King Jesus''; ''The Golden Fleece''; and ''Count Belisarius

''Count Belisarius'' is a historical novel by Robert Graves, first published in 1938, recounting the life of the Byzantine general Belisarius (AD 500–565).

Just as Graves's Claudius novels (''I, Claudius'' and ''Claudius the God and His Wi ...

''. He also was a prominent translator of Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later periods ...

and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

texts; his versions of ''The Twelve Caesars

''De vita Caesarum'' (Latin; "About the Life of the Caesars"), commonly known as ''The Twelve Caesars'', is a set of twelve biographies of Julius Caesar and the first 11 emperors of the Roman Empire written by Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. The g ...

'' and ''The Golden Ass

The ''Metamorphoses'' of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as ''The Golden Ass'' (''Asinus aureus''), is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius. At the end of the no ...

'' remain popular for their clarity and entertaining style. Graves was awarded the 1934 James Tait Black Memorial Prize

The James Tait Black Memorial Prizes are literary prizes awarded for literature written in the English language. They, along with the Hawthornden Prize, are Britain's oldest literary awards. Based at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, Uni ...

for both ''I, Claudius'' and ''Claudius the God

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Rom ...

''.

Early life

Graves was born into a middle-class family inWimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* ...

, then part of Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, now part of south London. He was the third of five children born to Alfred Perceval Graves

Alfred Perceval Graves (22 July 184627 December 1931), was an Anglo-Irish poet, songwriter and folklorist. He was the father of British poet and critic Robert Graves.

Early life

Graves was born in Dublin and was the son of The Rt Rev. Cha ...

(1846–1931), who was the sixth child and second son of Charles Graves, Bishop of Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe

The Bishop of Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe was the Ordinary of the Church of Ireland diocese of Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe, which was in the Province of Cashel until 1833, then afterwards in the Province of Dublin.

History

The title was ...

. His father was an Irish school inspector, Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

scholar and the author of the popular song "Father O'Flynn", and his mother was his father's second wife, Amalie Elisabeth Sophie von Ranke (1857–1951), the niece of the historian Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis of ...

.

At the age of seven, double pneumonia

Pneumonia can be classified in several ways, most commonly by where it was acquired (hospital versus community), but may also by the area of lung affected or by the causative organism. There is also a combined clinical classification, which combi ...

following measles almost took Graves's life, the first of three occasions when he was despaired of by his doctors as a result of afflictions of the lungs, the second being the result of a war wound and the third when he contracted Spanish influenza

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

in late 1918, immediately before demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milit ...

. At school, Graves was enrolled as Robert von Ranke Graves, and in Germany his books are published under that name, but before and during the First World War the name caused him difficulties.

In August 1916 an officer who disliked him spread the rumour that he was the brother of a captured German spy who had assumed the name " Karl Graves". The problem resurfaced in a minor way in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, when a suspicious rural policeman blocked his appointment to the Special Constabulary

The Special Constabulary is the part-time volunteer section of statutory police forces in the United Kingdom and some Crown dependencies. Its officers are known as special constables.

Every United Kingdom territorial police force has a specia ...

. Graves's eldest half-brother, Philip Perceval Graves, achieved success as a journalist and his younger brother, Charles Patrick Graves, was a writer and journalist.Richard Perceval Graves, "Graves, Robert von Ranke (1895–1985)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004; online ed., May 2010 �accessed 27 July 2010

/ref>

Education

Graves received his early education at a series of six preparatory schools, includingKing's College School

King's College School, also known as Wimbledon, KCS, King's and KCS Wimbledon, is a public school in Wimbledon, southwest London, England. The school was founded in 1829 by King George IV, as the junior department of King's College London an ...

in Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* ...

, Penrallt in Wales, Hillbrow School in Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

, Rokeby School

Rokeby School is an 11–16 secondary school for boys located in Canning Town, Greater London, England.

In 2010 the school relocated to new building on the Barking Road. Facilities at the school include technology and ICT rooms, a six court ...

in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

and Copthorne in Sussex, from which last in 1909 he won a scholarship to Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

. There he began to write poetry, and took up boxing, in due course becoming school champion at both welter- and middleweight

Middleweight is a weight class in combat sports.

Boxing Professional

In professional boxing, the middleweight division is contested above and up to .

Early boxing history is less than exact, but the middleweight designation seems to have be ...

. He claimed that this was in response to persecution because of the German element in his name, his outspokenness, his scholarly and moral seriousness, and his poverty relative to the other boys. He also sang in the choir, meeting there an aristocratic boy three years younger, G. H. "Peter" Johnstone, with whom he began an intense romantic friendship, the scandal of which led ultimately to an interview with the headmaster. However, Graves himself called it "chaste and sentimental" and "proto-homosexual," and though he was clearly in love with "Peter" (disguised by the name "Dick" in ''Good-Bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I ha ...

''), he denied that their relationship was ever sexual. He was warned about Peter's morals by other contemporaries. Among the masters his chief influence was George Mallory

George Herbert Leigh Mallory (18 June 1886 – 8 or 9 June 1924) was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s.

Born in Cheshire, Mallory became a student at Winchest ...

, who introduced him to contemporary literature and took him mountaineering in the holidays. In his final year at Charterhouse, he won a classical exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibition ...

to St John's College, Oxford, but did not take his place there until after the war.

First World War

At the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, Graves enlisted almost immediately, taking a commission in the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designate ...

as a second lieutenant (on probation) on 12 August. He was confirmed in his rank on 10 March 1915, and received rapid promotion, being promoted to lieutenant on 5 May 1915 and to captain on 26 October. He published his first volume of poems, ''Over the Brazier'', in 1916. He developed an early reputation as a war poet and was one of the first to write realistic poems about the experience of frontline conflict. In later years, he omitted his war poems from his collections, on the grounds that they were too obviously "part of the war poetry boom." At the Battle of the Somme, he was so badly wounded by a shell-fragment through the lung that he was expected to die and was officially reported as having died of wounds. He gradually recovered and, apart from a brief spell back in France, spent the remainder of the war in England.

One of Graves's friends at this time was the poet Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both describ ...

, a fellow officer in his regiment. They both convalesced at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. Among its alumnae have been Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, Dorothy Hodgkin, Ir ...

, which was used as a hospital for officers. "How unlike you to crib my idea of going to the Ladies' College at Oxford," Sassoon wrote to him in 1917.

At Somerville College, Graves met and fell in love with Marjorie, a nurse and professional pianist, but stopped writing to her once he learned she was engaged. About his time at Somerville, he wrote: "I enjoyed my stay at Somerville. The sun shone, and the discipline was easy."

In 1917, Sassoon rebelled against the conduct of the war by making a public anti-war statement. Graves feared Sassoon could face a court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

and intervened with the military authorities, persuading them that Sassoon was experiencing shell shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a react ...

and that they should treat him accordingly. As a result, Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart

Craiglockhart (; gd, Creag Longairt) is a suburb in the south west of Edinburgh, Scotland, lying between Colinton to the south, Morningside to the east Merchiston to the north east, and Longstone and Kingsknowe to the west. The Water of Leith ...

, a military hospital in Edinburgh, where he was treated by Dr. W. H. R. Rivers and met fellow patient Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced b ...

. Graves was treated here as well. Graves also had shell shock, or neurasthenia

Neurasthenia (from the Ancient Greek νεῦρον ''neuron'' "nerve" and ἀσθενής ''asthenés'' "weak") is a term that was first used at least as early as 1829 for a mechanical weakness of the nerves and became a major diagnosis in North A ...

as it was then called, but he was never hospitalised for it:

I thought of going back to France, but realized the absurdity of the notion. Since 1916, the fear of gas obsessed me: any unusual smell, even a sudden strong scent of flowers in a garden, was enough to send me trembling. And I couldn't face the sound of heavy shelling now; the noise of a car back-firing would send me flat on my face, or running for cover.The friendship between Graves and Sassoon is documented in Graves's letters and biographies; the story is fictionalised in

Pat Barker

Patricia Mary W. Barker, (née Drake; born 8 May 1943) is an English writer and novelist. She has won many awards for her fiction, which centres on themes of memory, trauma, survival and recovery. Her work is described as direct, blunt and pl ...

's novel ''Regeneration

Regeneration may refer to:

Science and technology

* Regeneration (biology), the ability to recreate lost or damaged cells, tissues, organs and limbs

* Regeneration (ecology), the ability of ecosystems to regenerate biomass, using photosynthesis

...

''. Barker also addresses Graves's experiences with homosexuality in his youth; at the end of the novel Graves asserts that his "affections have been running in more normal channels" after a friend was accused of "soliciting" with another man. The intensity of their early relationship is demonstrated in Graves's collection ''Fairies and Fusiliers

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic mythology, Celtic, Slavic paganism, Slavic, Germanic folklore, Germanic, ...

'' (1917), which contains many poems celebrating their friendship. Sassoon remarked upon a "heavy sexual element" within it, an observation supported by the sentimental nature of much of the surviving correspondence between the two men. Through Sassoon, Graves became a friend of Wilfred Owen, "who often used to send me poems from France."

In September 1917, Graves was seconded for duty with a garrison battalion. Graves's army career ended dramatically with an incident which could have led to a charge of desertion. Having been posted to Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

in late 1918, he "woke up with a sudden chill, which I recognized as the first symptoms of Spanish influenza

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

." "I decided to make a run for it," he wrote, "I should at least have my influenza in an English, and not an Irish, hospital." Arriving at Waterloo with a high fever but without the official papers that would secure his release from the army, he chanced to share a taxi with a demobilisation officer also returning from Ireland, who completed his papers for him with the necessary secret codes.

Postwar

Immediately after the war, Graves with his wife, Nancy Nicholson had a growing family, but he was financially insecure and weakened physically and mentally:

Immediately after the war, Graves with his wife, Nancy Nicholson had a growing family, but he was financially insecure and weakened physically and mentally:

Very thin, very nervous and with about four years' loss of sleep to make up, I was waiting until I got well enough to go to Oxford on the Government educational grant. I knew that it would be years before I could face anything but a quiet country life. My disabilities were many: I could not use a telephone, I felt sick every time I travelled by train, and to see more than two new people in a single day prevented me from sleeping. I felt ashamed of myself as a drag on Nancy, but had sworn on the very day of my demobilization never to be under anyone's orders for the rest of my life. Somehow I must live by writing.In October 1919, he took up his place at the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, soon changing course to English Language and Literature, though managing to retain his Classics exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibition ...

. In consideration of his health, he was permitted to live a little outside Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, on Boars Hill

Boars Hill is a Hamlet (place), hamlet southwest of Oxford, straddling the boundary between the Civil parishes in England, civil parishes of Sunningwell and Wootton, Vale of White Horse, Wootton. Historically, part of Berkshire until the Local ...

, where the residents included Robert Bridges

Robert Seymour Bridges (23 October 1844 – 21 April 1930) was an English poet who was Poet Laureate from 1913 to 1930. A doctor by training, he achieved literary fame only late in life. His poems reflect a deep Christian faith, and he is ...

, John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ...

(his landlord), Edmund Blunden

Edmund Charles Blunden (1 November 1896 – 20 January 1974) was an English poet, author, and critic. Like his friend Siegfried Sassoon, he wrote of his experiences in World War I in both verse and prose. For most of his career, Blunden was a ...

, Gilbert Murray

George Gilbert Aimé Murray (2 January 1866 – 20 May 1957) was an Australian-born British classical scholar and public intellectual, with connections in many spheres. He was an outstanding scholar of the language and culture of Ancient Greece ...

and Robert Nichols. Later, the family moved to Worlds End Cottage on Collice Street, Islip

Islip may refer to:

Places England

* Islip, Northamptonshire

*Islip, Oxfordshire

United States

*Islip, New York, a town in Suffolk County

** Islip (hamlet), New York, located in the above town

**Central Islip, New York, a hamlet and census-d ...

, Oxfordshire. His most notable Oxford companion was T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

, then a Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of All Souls', with whom he discussed contemporary poetry and shared in the planning of elaborate pranks. By this time, he had become an atheist. His work was part of the literature event in the art competition at the 1924 Summer Olympics

The 1924 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1924), officially the Games of the VIII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIIe olympiade) and also known as Paris 1924, were an international multi-sport event held in Paris, France. The op ...

.

While still an undergraduate he established a grocers shop on the outskirts of Oxford but the business soon failed. He also failed his BA degree but was exceptionally permitted to take a B.Litt. Bachelor of Letters (BLitt or LittB; Latin ' or ') is a second undergraduate university degree in which students specialize in an area of study relevant to their own personal, professional, or academic development. This area of study may have been t ...

by dissertation instead, allowing him to pursue a teaching career. In 1926, he took up a post as a Professor of English Literature at Cairo University

Cairo University ( ar, جامعة القاهرة, Jāmi‘a al-Qāhira), also known as the Egyptian University from 1908 to 1940, and King Fuad I University and Fu'ād al-Awwal University from 1940 to 1952, is Egypt's premier public university ...

, accompanied by his wife, their children and the poet Laura Riding

Laura Riding Jackson (born Laura Reichenthal; January 16, 1901 – September 2, 1991), best known as Laura Riding, was an American poet, critic, novelist, essayist and short story writer.

Early life

She was born in New York City to Nathan ...

. Graves later claimed that one of his pupils was a young Gamal Abdel Nasser. He returned to London briefly, where he separated from his wife under highly emotional circumstances (at one point Riding attempted suicide) before leaving to live with Riding in Deià, Majorca. There they continued to publish letterpress books under the rubric of the Seizin Press

The Seizin Press was a small press, founded in 1927 by Laura Riding and Robert Graves in London from 1928 until 1935. From 1930 it was based in Majorca.

Besides work by Graves and Riding, the Seizin Press published works by Gertrude Stein, Len L ...

, founded and edited the literary journal, ''Epilogue'' and wrote two successful academic books together: ''A Survey of Modernist Poetry'' (1927) and ''A Pamphlet Against Anthologies'' (1928); both had great influence on modern literary criticism, particularly New Criticism.

Literary career

In 1927, he published ''Lawrence and the Arabs'', a commercially successful biography ofT. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

. The autobiographical ''Good-Bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I ha ...

'' (1929, revised by him and republished in 1957) proved a success but cost him many of his friends, notably Siegfried Sassoon. In 1934, he published his most commercially successful work, ''I, Claudius

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Ro ...

''. Using classical sources (under the advice of classics scholar Eirlys Roberts

Eirlys Rhiwen Cadwaladr Roberts (3 January 1911 – 18 March 2008) was a Welsh consumer advocate and campaigner, and a co-founder of the Consumers' Association. She edited ''Which?'' magazine from 1957 to 1973.

Early life

Roberts was born in ...

) he constructed a complex and compelling tale of the life of the Roman emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

, a tale extended in the sequel ''Claudius the God

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Rom ...

'' (1935). ''I, Claudius'' received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize

The James Tait Black Memorial Prizes are literary prizes awarded for literature written in the English language. They, along with the Hawthornden Prize, are Britain's oldest literary awards. Based at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, Uni ...

in 1934. The Claudius books were turned into the very popular television series ''I, Claudius

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Ro ...

'', with Sir Derek Jacobi shown in both Britain and United States in the 1970s. Another historical novel by Graves, ''Count Belisarius

''Count Belisarius'' is a historical novel by Robert Graves, first published in 1938, recounting the life of the Byzantine general Belisarius (AD 500–565).

Just as Graves's Claudius novels (''I, Claudius'' and ''Claudius the God and His Wi ...

'' (1938), recounts the career of the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

general Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terr ...

.

Graves and Riding left Majorca in 1936 at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

and in 1939, they moved to the United States, taking lodging in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Their volatile relationship and eventual breakup was described by Robert's nephew Richard Perceval Graves in ''Robert Graves: 1927–1940: the Years with Laura'', and T. S. Matthews

Thomas Stanley Matthews (January 16, 1901 – January 4, 1991) was an American magazine editor, journalist, and writer. He served as editor of ''Time'' magazine from 1949 to 1953.

Background

Thomas Stanley Matthews was born on January 16, 1901 ...

's ''Jacks or Better'' (1977). It was also the basis for Miranda Seymour

Miranda Jane Seymour (born 8 August 1948) is an English literary critic, novelist and biographer. The lives she has described have included those of Robert Graves and Mary Shelley. Seymour, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, has in r ...

's novel ''The Summer of '39'' (1998).

After returning to Britain, Graves began a relationship with Beryl Hodge, the wife of Alan Hodge, his collaborator on '' The Long Week-End'' (1940) and '' The Reader Over Your Shoulder'' (1943; republished in 1947 as ''The Use and Abuse of the English Language'' but subsequently republished several times under its original title). Graves and Beryl (they were not to marry until 1950) lived in Galmpton, Torbay

Galmpton is a semi-rural village in Torbay, in the ceremonial county of Devon, England. It is located in the ward of Churston-with-Galmpton and the historic civil parish of Churston Ferrers, though some areas historically considered parts o ...

until 1946, when they re-established a home with their three children, in Deià, Majorca. The house is now a museum. The year 1946 also saw the publication of his historical novel '' King Jesus''. He published ''The White Goddess

''The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth'' is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by author and poet Robert Graves. First published in 1948, the book is based on earlier articles published in ''Wales'' magaz ...

: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth'' in 1948; it is a study of the nature of poetic inspiration, interpreted in terms of the classical and Celtic mythology he knew so well. He turned to science fiction with ''Seven Days in New Crete

''Seven Days in New Crete'', also known as ''Watch the North Wind Rise'', is a seminal future-utopian speculative fiction novel by Robert Graves, first published in 1949. It shares many themes and ideas with Graves' ''The White Goddess'', pub ...

'' (1949) and in 1953 he published ''The Nazarene Gospel Restored'' with Joshua Podro. He also wrote '' Hercules, My Shipmate'', published under that name in 1945 (but first published as ''The Golden Fleece'' in 1944).

In 1955, he published ''The Greek Myths

''The Greek Myths'' (1955) is a mythography, a compendium of Greek mythology, with comments and analyses, by the poet and writer Robert Graves. Many editions of the book separate it into two volumes. Abridged editions of the work contain only the ...

'', which retells a large body of Greek myths, each tale followed by extensive commentary drawn from the system of ''The White Goddess''. His retellings are well respected; many of his unconventional interpretations and etymologies are dismissed by classicists. Graves in turn dismissed the reactions of classical scholars, arguing that they are too specialised and "prose-minded" to interpret "ancient poetic meaning," and that "the few independent thinkers ... rethe poets, who try to keep civilisation alive."

He published a volume of short stories, ''¡Catacrok! Mostly Stories, Mostly Funny'', in 1956. In 1961, he became Professor of Poetry at Oxford, a post he held until 1966.

In 1967, Robert Graves published, together with Omar Ali-Shah

Omar Ali-Shah ( hi, ओमर अली शाह, ur, عمر علی شاہ, nq; 19227 September 2005) was a prominent exponent of modern Naqshbandi Sufism. He wrote a number of books on the subject, and was head of a large number of Sufi groups ...

, a new translation of the ''Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

''Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám'' is the title that Edward FitzGerald gave to his 1859 translation from Persian to English of a selection of quatrains (') attributed to Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), dubbed "the Astronomer-Poet of Persia".

Altho ...

''.Stuffed Eagle''Time'', 31 May 1968 The translation quickly became controversial; Graves was attacked for trying to break the spell of famed passages in Edward FitzGerald's Victorian translation, and L. P. Elwell-Sutton, an orientalist at

Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

, maintained that the manuscript used by Ali-Shah and Graves, which Ali-Shah and his brother Idries Shah

Idries Shah (; hi, इदरीस शाह, ps, ادريس شاه, ur, ; 16 June 1924 – 23 November 1996), also known as Idris Shah, né Sayed Idries el- Hashimi (Arabic: سيد إدريس هاشمي) and by the pen name Ark ...

claimed had been in their family for 800 years, was a forgery. The translation was a critical disaster and Graves's reputation suffered severely due to what the public perceived as his gullibility in falling for the Shah brothers' deception.

In 1968, Graves was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

. His private audience with the Queen was shown in the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

, which aired in 1969.

From the 1960s until his death, Robert Graves frequently exchanged letters with Spike Milligan

Terence Alan "Spike" Milligan (16 April 1918 – 27 February 2002) was an Irish actor, comedian, writer, musician, poet, and playwright. The son of an English mother and Irish father, he was born in British Raj, British Colonial India, where h ...

. Many of their letters to each other are collected in the book ''Dear Robert, Dear Spike''.

On 11 November 1985, Graves was among sixteen Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

's Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

. The inscription on the stone was written by friend and fellow Great War poet Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced b ...

. It reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity." Of the 16 poets, Graves was the only one still living at the time of the commemoration ceremony.

UK government documents released in 2012 indicate that Graves turned down a CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in 1957. In 2012, the Nobel Records were opened after 50 years, and it was revealed that Graves was among a shortlist of authors considered for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

, along with John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

(who was that year's recipient of the prize), Lawrence Durrell

Lawrence George Durrell (; 27 February 1912 – 7 November 1990) was an expatriate British novelist, poet, dramatist, and travel writer. He was the eldest brother of naturalist and writer Gerald Durrell.

Born in India to British colonial p ...

, Jean Anouilh

Jean Marie Lucien Pierre Anouilh (; 23 June 1910 – 3 October 1987) was a French dramatist whose career spanned five decades. Though his work ranged from high drama to absurdist farce, Anouilh is best known for his 1944 play ''Antigone'', an a ...

and Karen Blixen. Graves was rejected because, even though he had written several historical novels, he was still primarily seen as a poet, and committee member Henry Olsson was reluctant to award any Anglo-Saxon poet the prize before the death of Ezra Pound, believing that other writers did not match his talent.

In 2017, Seven Stories Press began its Robert Graves Project. Fourteen of Graves's out-of-print books were to be republished.

His religious belief has been examined by Patrick Grant, "Belief in anarchy: Robert Graves as mythographer," in ''Six Modern Authors and Problems of Belief''.

Sexuality

Robert Graves wasbisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, whi ...

, having intense romantic relationships with both men and women, though the word he coined for it was "pseudo-homosexual." Graves was raised to be "prudishly innocent, as my mother had planned I should be." His mother, Amy, forbade speaking about sex, save in a "gruesome" context, and all skin "must be covered." At his days in Penrallt, he had "innocent crushes" on boys; one in particular was a boy named Ronny, who "climbed trees, killed pigeons with a catapult and broke all the school rules while never seeming to get caught." At Charterhouse, an all-boys school, it was common for boys to develop "amorous but seldom erotic" relationships, which the headmaster mostly ignored. Graves described boxing with a friend, Raymond Rodakowski, as having a "a lot of sex feeling". And although Graves admitted to loving Raymond, he would dismiss it as "more comradely than amorous."Graves (2014), p. 70

In his fourth year at Charterhouse, Graves would meet "Dick" (George "Peter" Harcourt Johnstone) with whom he would develop "an even stronger relationship". Johnstone was an object of adoration in Graves's early poems. Graves's feelings for Johnstone were exploited by bullies, who led Graves to believe that Johnstone was seen kissing the choir-master. Graves, jealous, demanded the choir-master's resignation. During the First World War, Johnstone remained a "solace" to Graves. Despite Graves's own "pure and innocent" view of Johnstone, Graves's cousin Gerald wrote in a letter that Johnstone was: "not at all the innocent fellow I took him for, but as bad as anyone could be". Johnstone remained a subject for Graves's poems despite this. Communication between them ended when Johnstone's mother found their letters and forbade further contact with Graves. Johnstone would later be arrested for attempting to seduce a Canadian soldier, which removed Graves's denial about Johnstone's infidelity, causing Graves to collapse.

In 1917, Graves met Marjorie Machin, an auxiliary nurse from Kent. He admired her "direct manner and practical approach to life". Graves did not pursue the relationship when he realised Machin had a fiancé on the Front.Seymour (2003), p. 63 This began a period where Graves would begin to take interest in women with more masculine traits. Nancy Nicholson, his future wife, was an ardent feminist: she kept her hair short, wore trousers, and had "boyish directness and youth." Her feminism never conflicted with Graves's own ideas of female superiority. Siegfried Sassoon, who felt as if Graves and he had a relationship of a fashion, felt betrayed by Graves's new relationship and declined to go to the wedding. Graves apparently never loved Sassoon in the same fashion that Sassoon loved Graves.

Graves's and Nicholson's marriage was strained, with Graves living with "shell shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a react ...

", and having an insatiable need for sex, which Nicholson did not reciprocate. Nancy forbade any mention of the war, which added to the conflict. In 1926, he would meet Laura Riding, with whom he would run away in 1929 while still married to Nicholson. Prior to this, Graves, Riding and Nicholson would attempt a triadic relationship called "The Trinity." Despite the implications, Riding and Nicholson were most likely heterosexual. This triangle became the "Holy Circle" with the addition of Irish poet Geoffrey Phibbs

Jeoffrey "Geoffrey" Basil Phibbs (1900–1956) was an English-born Irish poet; he took his mother's name and called himself Geoffrey Taylor, after about 1930.

Phibbs was born in Smallburgh, Norfolk. He was brought up in Sligo, and educated ...

, who himself was still married to Irish artist Norah McGuinness

Norah Allison McGuinness (7 November 1901 – 22 November 1980) was an Irish painter and illustrator.

Early life

Norah McGuinness was born in County Londonderry. She attended life classes at Derry Technical School and from 1921 studied at ...

. This relationship revolved around the worship and reverence of Riding. Graves and Phibbs were both to sleep with Riding. When Phibbs attempted to leave the relationship, Graves was sent to track him down, even threatening to kill Phibbs if he did not return to the circle. When Phibbs resisted, Riding threw herself out of a window, with Graves following suit to reach her. Graves's commitment to Riding was so strong that he entered, on her word, a period of enforced celibacy, "which he had not enjoyed".

By 1938, no longer entranced by Riding, Graves fell in love with the then-married Beryl Hodge. In 1950, after much dispute with Nicholson (whom he had not divorced yet), he married Beryl. Despite having a loving marriage with Beryl, Graves would take on a 17-year-old muse, Judith Bledsoe, in 1950. Although the relationship would be described as "not overtly sexual", Graves would later in 1952 attack Judith's new fiancé, getting the police called on him in the process. He would later have three successive female muses, who came to dominate his poetry.

Death and legacy

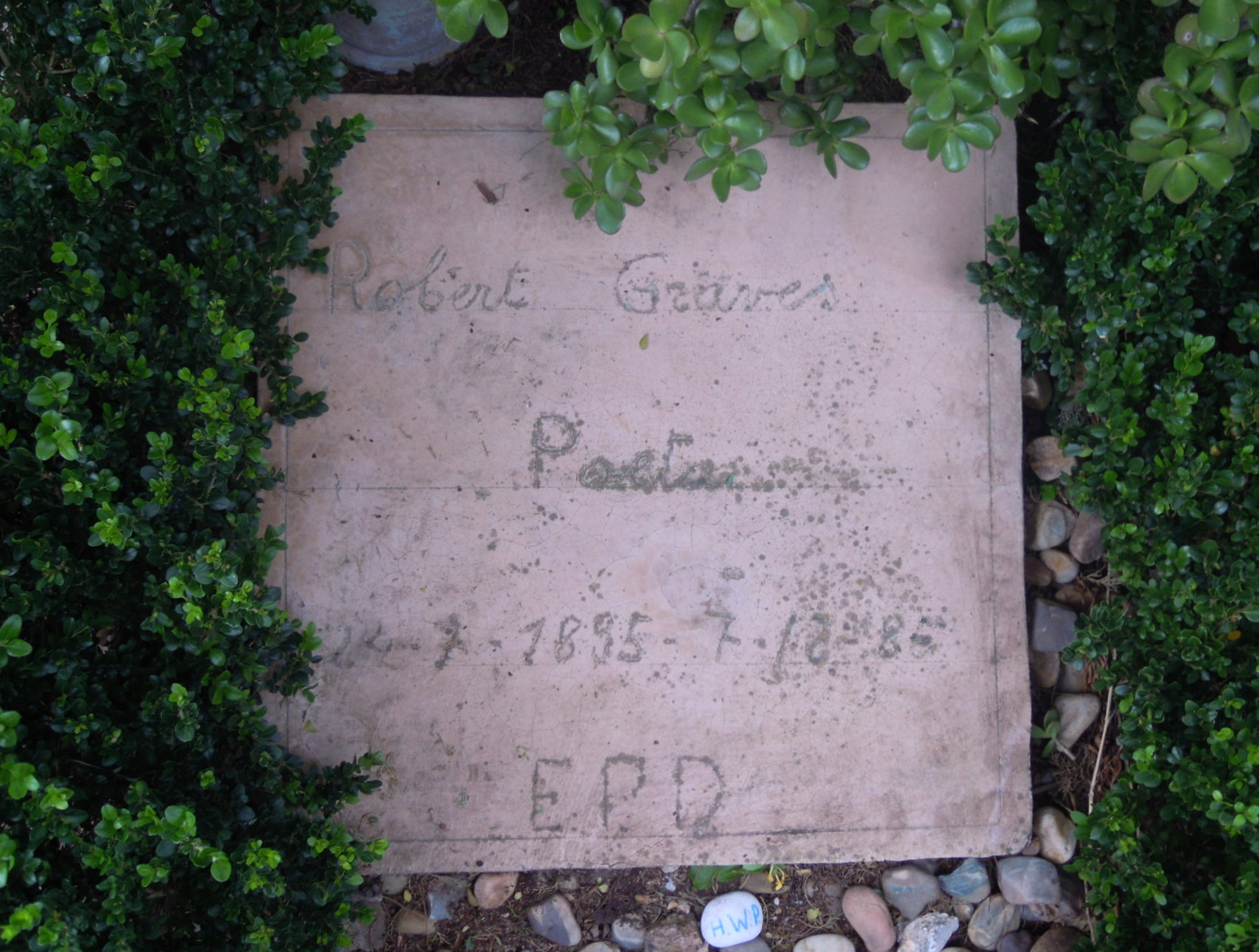

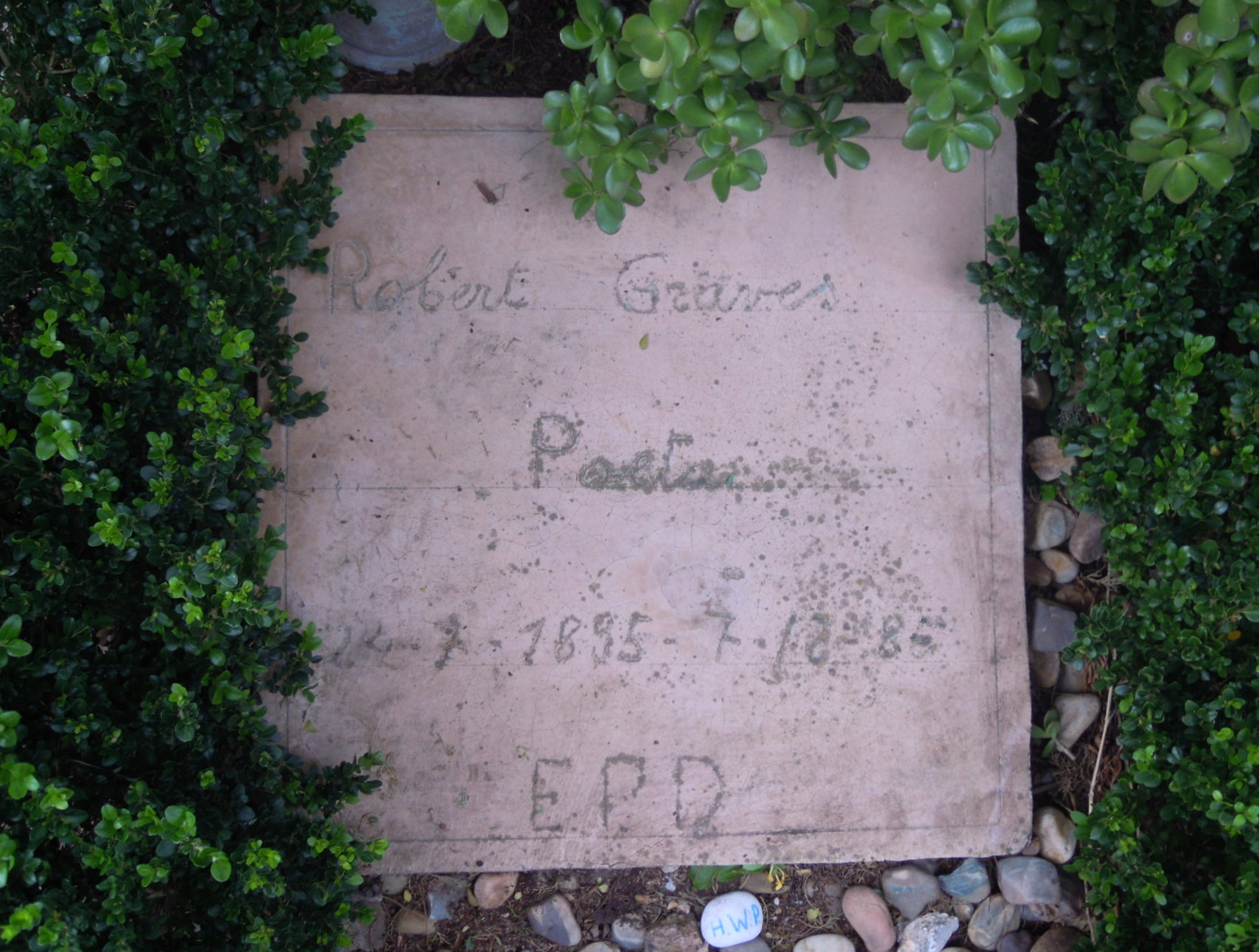

Death

During the early 1970s, Graves began to experience increasingly severe memory loss. By his 80th birthday in 1975, he had come to the end of his working life. He lived for another decade, in an increasingly dependent condition, until he died from heart failure on 7 December 1985 at the age of 90 years. His body was buried the next morning in the small churchyard on a hill at Deià, at the site of a shrine that had once been sacred tothe White Goddess

''The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth'' is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by author and poet Robert Graves. First published in 1948, the book is based on earlier articles published in ''Wales'' magaz ...

of Pelion

Pelion or Pelium (Modern el, Πήλιο, ''Pílio''; Ancient Greek/ Katharevousa: Πήλιον, ''Pēlion'') is a mountain at the southeastern part of Thessaly in northern Greece, forming a hook-like peninsula between the Pagasetic Gulf and the ...

. His second wife, Beryl Graves, died on 27 October 2003 and her body was interred in the same grave.

Memorials

Three of his former houses have ablue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

on them: in Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* ...

, Brixham, and Islip

Islip may refer to:

Places England

* Islip, Northamptonshire

*Islip, Oxfordshire

United States

*Islip, New York, a town in Suffolk County

** Islip (hamlet), New York, located in the above town

**Central Islip, New York, a hamlet and census-d ...

.

Children

Graves had eight children. With his first wife, Nancy Nicholson, he had Jennie (who married journalistAlexander Clifford

Alexander G. Clifford (1909 – 1952) was a British journalist and author, best known as a war correspondent during World War II.

Life

Clifford was educated at Charterhouse School and Balliol College, Oxford. He married the actress and journa ...

), David (who was killed in the Second World War), Catherine (who married nuclear scientist Clifford Dalton at Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alder ...

), and Sam. With his second wife, Beryl Pritchard (1915–2003), he had William (author of the well-received memoir ''Wild Olives: Life on Majorca with Robert Graves''), Lucia (a translator and author whose versions of novels by Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Carlos Ruiz Zafón (; 25 September 1964 – 19 June 2020) was a Spanish novelist known for his 2001 novel ''La sombra del viento'' ('' The Shadow of the Wind'').

Biography

Ruiz Zafón was born in Barcelona. His grandparents had worked in a fa ...

have been quite successful commercially), Juan (addressed in one of Robert Graves' most famous and critically praised poems, "To Juan at the Winter Solstice"), and Tomás (a writer and musician).

Bibliography

Poetry collections

* ''Over the Brazier''. London: The Poetry Bookshop, 1916; New York: Alfred. A. Knopf, 1923. * ''Goliath and David''. London: Chiswick Press, 1916. * ''Country Sentiment'', London: Martin Secker, 1920; New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1920 * ''The Feather Bed.'' Richmond, Surrey: Hogarth Press, 1923. * ''Mock Beggar Hall.'' London: Hogarth Press, 1924. * ''Welchmans Hose.'' London: The Fleuron, 1925. * ''Poems.'' London: Ernest Benn, 1925. * ''The Marmosites Miscellany'' (as John Doyle). London: Hogarth Press, 1925. * ''Poems (1914–1926)''. London: William Heinemann, 1927; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1929. * ''Poems (1914–1927)''. London: William Heinemann * ''To Whom Else?'' Deyá, Majorca: Seizin Press, 1931. * ''Poems 1930–1933.'' London: Arthur Barker, 1933. * ''Collected Poems.'' London: Cassell, 1938; New York: Random House, 1938. * ''No More Ghosts: Selected Poems.'' London: Faber & Faber, 1940. * ''Work in Hand'', with Norman Cameron and Alan Hodge. London: Hogarth Press, 1942. * ''Poems''. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1943. * ''Poems 1938–1945''. London: Cassell, 1945; New York: Creative Age Press, 1946. * ''Collected Poems (1914–1947)''. London: Cassell, 1948. * ''Poems and Satires''. London: Cassell, 1951. * ''Poems 1953''. London: Cassell, 1953. * ''Collected Poems 1955''. New York: Doubleday, 1955. * ''Poems Selected by Himself''. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957; rev. 1961, 1966, 1972, 1978. * ''The Poems of Robert Graves''. New York: Doubleday, 1958. * ''Collected Poems 1959''. London: Cassell, 1959. * ''The Penny Fiddle: Poems for Children''. London: Cassell, 1960; New York: Doubleday, 1961. * ''More Poems 1961''. London: Cassell, 1961. * ''Collected Poems''. New York: Doubleday, 1961. * ''New Poems 1962''. London: Cassell, 1962; as ''New Poems''. New York: Doubleday, 1963. * ''The More Deserving Cases: Eighteen Old Poems for Reconsideration''. Marlborough College Press, 1962. * ''Man Does, Woman Is''. London: Cassell, 1964/New York:Doubleday, 1964. * ''Ann at Highwood Hall: Poems for Children''. London: Cassell, 1964; New York: Triangle Square, 2017. * ''Love Respelt''. London: Cassell, 1965/New York: Doubleday, 1966. * ''Collected Poems, 1965''. London: Cassell, 1965. * ''Seventeen Poems Missing from "Love Respelt"''. privately printed, 1966. * ''Colophon to "Love Respelt"''. Privately printed, 1967. * ''Poems 1965–1968''. London: Cassell, 1968; New York: Doubleday, 1969. * ''Poems About Love''. London: Cassell, 1969; New York: Doubleday, 1969. * ''Love Respelt Again''. New York: Doubleday, 1969. * ''Beyond Giving''. privately printed, 1969. * ''Poems 1968–1970''. London: Cassell, 1970; New York: Doubleday, 1971. * ''The Green-Sailed Vessel''. privately printed, 1971. * ''Poems: Abridged for Dolls and Princes''. London: Cassell, 1971. * ''Poems 1970–1972''. London: Cassell, 1972; New York: Doubleday, 1973. * ''Deyá, A Portfolio''. London: Motif Editions, 1972. * ''Timeless Meeting: Poems''. privately printed, 1973. * ''At the Gate''. privately printed, London, 1974. * ''Collected Poems 1975''. London: Cassell, 1975. * ''New Collected Poems''. New York: Doubleday, 1977. * ''Selected Poems'', ed.Paul O'Prey

Paul Gerard O'Prey is a British academic leader and author. In 2019 he was appointed chair of the Edward James Foundation, which owns a large rural estate in the South Downs and runs West Dean College of Arts and Conservation. Between 2004 an ...

. London: Penguin, 1986

* ''The Centenary Selected Poems'', ed. Patrick Quinn. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1995.

* ''Complete Poems Volume 1'', ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1995.

* ''Complete Poems Volume 2'', ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1996.

* ''Complete Poems Volume 3'', ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1999.

* ''The Complete Poems in One Volume'', ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester: Penguin Books

Penguin Books is a British publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers The Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the following year.Faber & Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel ...

, 2012.

Fiction

* ''My Head! My Head!''. London: Secker, 1925; Alfred. A. Knopf, New York, 1925. * ''The Shout

''The Shout'' is a 1978 British horror film directed by Jerzy Skolimowski. It was based on a short story by Robert Graves and adapted for the screen by Skolimowski and Michael Austin. The film was the first to be produced by Jeremy Thomas under ...

''. London: Mathews & Marrot, 1929.

* ''No Decency Left''. (with Laura Riding) (as Barbara Rich). London: Jonathan Cape, 1932.

* ''The Real David Copperfield''. London: Arthur Barker, 1933; as ''David Copperfield'', by Charles Dickens, Condensed by Robert Graves, ed. M. P. Paine. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1934.

* ''I, Claudius

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Ro ...

''. London: Arthur Barker, 1934; New York: Smith & Haas, 1934.

** Sequel: ''Claudius the God and his Wife Messalina

''I, Claudius'' is a historical novel by English writer Robert Graves, published in 1934. Written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius, it tells the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early years of the Rom ...

''. London: Arthur Barker, 1934; New York: Smith & Haas, 1935.

* ''Antigua, Penny, Puce''. Deyá, Majorca/London: Seizin Press/Constable, 1936; New York: Random House, 1937.

* ''Count Belisarius

''Count Belisarius'' is a historical novel by Robert Graves, first published in 1938, recounting the life of the Byzantine general Belisarius (AD 500–565).

Just as Graves's Claudius novels (''I, Claudius'' and ''Claudius the God and His Wi ...

''. London: Cassell, 1938: Random House, New York, 1938.

* '' Sergeant Lamb of the Ninth''. London: Methuen, 1940; as ''Sergeant Lamb's America''. New York: Random House, 1940.

** Sequel: '' Proceed, Sergeant Lamb''. London: Methuen, 1941; New York: Random House, 1941.

* '' The Story of Marie Powell: Wife to Mr. Milton''. London: Cassell, 1943; as ''Wife to Mr Milton: The Story of Marie Powell''. New York: Creative Age Press, 1944.

* ''The Golden Fleece''. London: Cassell, 1944; as ''Hercules, My Shipmate'', New York: Creative Age Press, 1945; New York: Seven Stories Press, 2017.

* '' King Jesus. ''New York: Creative Age Press, 1946; London: Cassell, 1946.

* ''Watch the North Wind Rise''. New York: Creative Age Press, 1949; as ''Seven Days in New Crete

''Seven Days in New Crete'', also known as ''Watch the North Wind Rise'', is a seminal future-utopian speculative fiction novel by Robert Graves, first published in 1949. It shares many themes and ideas with Graves' ''The White Goddess'', pub ...

''. London: Cassell, 1949.

* ''The Islands of Unwisdom

''The Islands of Unwisdom'' is an historical novel by Robert Graves, published in 1949. It was also published in the UK as ''The Isles of Unwisdom''.

Plot

It is a reconstruction of an historic event, the voyage of Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira ...

''. New York: Doubleday, 1949; as ''The Isles of Unwisdom''. London: Cassell, 1950.

* ''Homer's Daughter

''Homer's Daughter'' is a 1955 novel by British author Robert Graves, famous for ''I, Claudius'' and ''The White Goddess''.

The novel starts from the idea that Homer's ''Odyssey'' was written by a princess in the Greek settlements in Sicily. Th ...

''. ''London: Cassell, 1955; New York: Doubleday, 1955; New York: Seven Stories Press, 2017.

* ''Catacrok! Mostly Stories, Mostly Funny''. London: Cassell, 1956.

* ''They Hanged My Saintly Billy''. London: Cassell, 1957; New York: Doubleday, 1957; New York, Seven Stories Press, 2017.

* ''Collected Short Stories''. Doubleday: New York, 1964; Cassell, London, 1965.

* ''An Ancient Castle''. London: Peter Owen, 1980.

Other works

* ''On English Poetry''. New York: Alfred. A. Knopf, 1922; London: Heinemann, 1922. * ''The Meaning of Dreams''. London: Cecil Palmer, 1924; New York: Greenberg, 1925. * ''Poetic Unreason and Other Studies''. London: Cecil Palmer, 1925. * ''Contemporary Techniques of Poetry: A Political Analogy''. London: Hogarth Press, 1925. * ''John Kemp's Wager: A Ballad Opera''. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1925. * ''Another Future of Poetry''. London: Hogarth Press, 1926. * ''Impenetrability or the Proper Habit of English''. London: Hogarth Press, 1927. * ''The English Ballad: A Short Critical Survey''. London: Ernest Benn, 1927; revised as ''English and Scottish Ballads''. London:William Heinemann

William Henry Heinemann (18 May 1863 – 5 October 1920) was an English publisher of Jewish descent and the founder of the Heinemann publishing house in London.

Early life

On 18 May 1863, Heinemann was born in Surbiton, Surrey, England. Heine ...

, 1957; New York: Macmillan, 1957.

* ''Lars Porsena or the Future of Swearing and Improper Language''. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1927; E. P. Dutton, New York, 1927; revised as ''The Future of Swearing and Improper Language''. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1936.

* ''A Survey of Modernist Poetry'' (with Laura Riding). London: William Heinemann, 1927; New York: Doubleday, 1928.

* ''Lawrence and the Arabs''. London: Jonathan Cape, 1927; as Lawrence and the Arabian Adventure. New York: Doubleday, 1928.

* ''A Pamphlet Against Anthologies'' (with Laura Riding). London: Jonathan Cape, 1928; as ''Against Anthologies''. New York: Doubleday, 1928.

* ''Mrs. Fisher or the Future of Humour''. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1928.

* ''Good-bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I ha ...

: An Autobiography''. London: Jonathan Cape, 1929; New York: Jonathan Cape and Smith, 1930; rev., New York: Doubleday, 1957; London: Cassell, 1957; Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1960.

* ''But It Still Goes On: An Accumulation''. London: Jonathan Cape, 1930; New York: Jonathan Cape and Smith, 1931.

* ''T. E. Lawrence to His Biographer Robert Graves''. New York: Doubleday, 1938; London: Faber & Faber, 1939.

* ''The Long Weekend'' (with Alan Hodge). London: Faber & Faber, 1940; New York: Macmillan, 1941.

* ''The Reader Over Your Shoulder'' (with Alan Hodge). London: Jonathan Cape, 1943; New York: Macmillan, 1943; New York, Seven Stories Press, 2017.

* ''The White Goddess

''The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth'' is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by author and poet Robert Graves. First published in 1948, the book is based on earlier articles published in ''Wales'' magaz ...

''. London: Faber & Faber, 1948; New York: Creative Age Press, 1948; rev., London: Faber & Faber, 1952, 1961; New York: Alfred. A. Knopf, 1958.

''The Common Asphodel: Collected Essays on Poetry 1922–1949''. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1949.

* ''Occupation: Writer''. New York: Creative Age Press, 1950; London: Cassell, 1951. * ''

The Golden Ass

The ''Metamorphoses'' of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as ''The Golden Ass'' (''Asinus aureus''), is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius. At the end of the no ...

of Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern- ...

'', New York: Farrar, Straus, 1951.

* ''The Nazarene Gospel Restored'' (with Joshua Podro). London: Cassell, 1953; New York: Doubleday, 1954.

* ''The Greek Myths

''The Greek Myths'' (1955) is a mythography, a compendium of Greek mythology, with comments and analyses, by the poet and writer Robert Graves. Many editions of the book separate it into two volumes. Abridged editions of the work contain only the ...

''. London: Penguin, 1955; Baltimore: Penguin, 1955.

* ''The Crowning Privilege: The Clark Lectures, 1954–1955''. London: Cassell, 1955; New York: Doubleday, 1956.

* ''Adam's Rib''. London: Trianon Press, 1955; New York: Yoseloff, 1958.

* ''Jesus in Rome'' (with Joshua Podro). London: Cassell, 1957.

* ''Steps''. London: Cassell, 1958.

* ''5 Pens in Hand''. New York: Doubleday, 1958.

* ''The Anger of Achilles''. New York: Doubleday, 1959.

* ''Food for Centaurs''. New York: Doubleday, 1960.

* ''Greek Gods and Heroes''. New York: Doubleday, 1960; as ''Myths of Ancient Greece''. London: Cassell, 1961.

* ''5 November address'', X magazine, Volume One, Number Three, June 1960; An Anthology from X'' (Oxford University Press 1988).

* ''Selected Poetry and Prose'' (ed. James Reeves). London: Hutchinson, 1961.

* ''Oxford Addresses on Poetry''. London: Cassell, 1962; New York: Doubleday, 1962.

* ''The Siege and Fall of Troy''. London: Cassell, 1962; New York: Doubleday, 1963; New York, Seven Stories Press, 2017.

* ''The Big Green Book''. New York: Crowell Collier, 1962; Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1978. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak

* ''Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis'' (with Raphael Patai

Raphael Patai (Hebrew רפאל פטאי; November 22, 1910 − July 20, 1996), born Ervin György Patai, was a Hungarian-Jewish ethnographer, historian, Orientalist and anthropologist.

Family background

Patai was born in Budapest, Austria-Hu ...

). New York: Doubleday, 1964; London: Cassell, 1964.

* ''Majorca Observed''. London: Cassell, 1965; New York: Doubleday, 1965.

* ''Mammon and the Black Goddess''. London: Cassell, 1965; New York: Doubleday, 1965.

* ''Two Wise Children''. New York: Harlin Quist

Harlin Quist (died May 13, 2000, age 69) born Harlin Bloomquist was a publisher noted for innovative children's books.

Early years

Harlin was born and raised in Virginia, Minnesota, attended Carnegie Tech and began his career in 1958 as an off-Br ...

, 1966; London: Harlin Quist

Harlin Quist (died May 13, 2000, age 69) born Harlin Bloomquist was a publisher noted for innovative children's books.

Early years

Harlin was born and raised in Virginia, Minnesota, attended Carnegie Tech and began his career in 1958 as an off-Br ...

, 1967.

* ''The Rubaiyyat of Omar Khayyam'' (with Omar Ali-Shah

Omar Ali-Shah ( hi, ओमर अली शाह, ur, عمر علی شاہ, nq; 19227 September 2005) was a prominent exponent of modern Naqshbandi Sufism. He wrote a number of books on the subject, and was head of a large number of Sufi groups ...

). London: Cassell, 1967.

* ''Poetic Craft and Principle''. London: Cassell, 1967.

* ''The Poor Boy Who Followed His Star''. London: Cassell, 1968; New York: Doubleday, 1969.

* ''Greek Myths and Legends''. London: Cassell, 1968.

* ''The Crane Bag''. London: Cassell, 1969.

* ''On Poetry: Collected Talks and Essays''. New York: Doubleday, 1969.

* ''Difficult Questions, Easy Answers''. London: Cassell, 1971; New York: Doubleday, 1973.

* ''In Broken Images: Selected Letters 1914–1946'', ed. Paul O'Prey

Paul Gerard O'Prey is a British academic leader and author. In 2019 he was appointed chair of the Edward James Foundation, which owns a large rural estate in the South Downs and runs West Dean College of Arts and Conservation. Between 2004 an ...

. London: Hutchinson, 1982

* ''Between Moon and Moon: Selected Letters 1946–1972'', ed. Paul O'Prey

Paul Gerard O'Prey is a British academic leader and author. In 2019 he was appointed chair of the Edward James Foundation, which owns a large rural estate in the South Downs and runs West Dean College of Arts and Conservation. Between 2004 an ...

. London: Hutchinson, 1984

* ''Life of the Poet Gnaeus Robertulus Gravesa'', ed. Beryl & Lucia Graves. Deià: The New Seizin Press, 1990

* ''Collected Writings on Poetry'', ed. Paul O'Prey

Paul Gerard O'Prey is a British academic leader and author. In 2019 he was appointed chair of the Edward James Foundation, which owns a large rural estate in the South Downs and runs West Dean College of Arts and Conservation. Between 2004 an ...

, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1995.

* ''Complete Short Stories'', ed. Lucia Graves

Lucia Graves (born 21 July 1943) is a writer and translator. Born in Devon, England, she is the daughter of writer Robert Graves, and his second wife, Beryl Pritchard (1915–2003).

Biography

Lucia is a translator working in English and Spanish/ ...

, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1995.

* ''Some Speculations on Literature, History, and Religion'', ed. Patrick Quinn, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2000.

See also

* * Joseph Campbell *Mircea Eliade

Mircea Eliade (; – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago. He was a leading interpreter of religious experience, who established paradigms in religiou ...

* James Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

* Margaret Murray

Margaret Alice Murray (13 July 1863 – 13 November 1963) was an Anglo-Indian Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, historian, and folklorist. The first woman to be appointed as a lecturer in archaeology in the United Kingdom, she work ...

Citations

General sources

* Graves, Robert (1960). ''Good-Bye to All That

''Good-Bye to All That'' is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I ha ...

'', London: Penguin.

* Seymour, Miranda (1995). ''Robert Graves: Life on the Edge'', London: Doubleday. .

External links

Robert Graves Trust and Society Information Portal

Robert Graves Foundation

Profile at Poetry Foundation

Profile, poems written and audio at poets.org

Profile, poems written and audio at Poetry Archive

Gallery of Graves's portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London

Papers of Robert Graves: Correspondence, 1915–1996

* Translated Penguin Books – a

Penguin First Editions

reference site of early first edition Penguin Books.

Works and archives

The Robert Graves Digital Archive

by the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

Robert Graves collection

at University of Victoria, Special Collections

Robert Graves Papers

at Southern Illinois University Carbondale Special Collections Research Center * * * William S. Reese Collection of Robert Graves. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. *

Articles and interviews

1965 BBC television interview

(29 mins) * *

* ttp://www.robertgravesoratorio.co.uk "The Cool Web: A Robert Graves Oratorio"– First World War commemoration piece based on texts from Robert Graves's poems {{DEFAULTSORT:Graves, Robert 1895 births 1985 deaths 20th-century atheists 20th-century British non-fiction writers 20th-century British poets 20th-century British short story writers 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English poets 20th-century translators Alumni of St John's College, Oxford Bisexual men Bisexual writers British Army personnel of World War I Cultural critics English atheists English expatriates in Spain English historical novelists English LGBT novelists English LGBT poets English literary critics English male non-fiction writers English male novelists English male poets English male short story writers English memoirists English people of German descent English people of Irish descent English short story writers English World War I poets Graves family James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Matriarchy Olympic competitors in art competitions Oxford Professors of Poetry People educated at Charterhouse School People educated at Copthorne Preparatory School People educated at King's College School, London People from Wimbledon, London People with post-traumatic stress disorder Prix Italia winners Royal Welch Fusiliers officers Translators of Omar Khayyám Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Writers of style guides Military personnel from Surrey